My sister Anne Raver walked along the edge of the curving driveway studying the plants.

Steve Danielovich, a forester, helped lay out the driveway. Last year, Steve admired the oaks and noticed that the one closest to the driveway has a huge root that stretches out into the roadway. He suggested we curve the driveway a little bit here to go around that root to protect the tree.

That curve creates a little patio of soil at the base of the oak. Last year, Claudia and I transplanted a dozen perennials from the old farmhouse gardens to temporary camps in this spot. Now, Anne and I had come to dig them up and move them to their new permanent homes around the little house.

“Those peonies look happy here. Let’s leave them,” Anne said. We decided to move the chives and the rosemary. I went back up the drive to get the tractor so we could carry the heavy root balls in its bucket.

When I got back, Anne was standing in the middle of the driveway, her head tilted back, eying the small orangey pale green oak leaves just opening overhead. I turned the engine off so we could hear each other

“Isn’t this driveway beautiful?” I boasted.

“You got the driveway right,” Anne agreed. She looked up again. “This area is going to be shady soon. Some of these plants love full sun.”

So we dug up the catnip and coreopsis too.

“We can’t move that baptisia. That root ball weighs a ton,” I said. “But let’s bring the turtle head.”

Building all new gardens at my age may seem ridiculous. It involves tremendous work, a dump truck load of compost, and hours of backbreaking digging. But last year as I packed books for the move to the new house, I realized that my plants were just as important, old friends I would want in my new home.

This spring the thought of building new beds for my friends seemed daunting, Trojan labors for the old lady. To avoid the work, I began with some annual vegetable homes. I used my new carpentry skills and hammered some leftover boards into two long boxes. I built them alongside Rudy’s long Veterans’ Administration ramp, sugar snap peas on one side, sunflowers on the other.

Then, in honor of my long past Uncle Robert and his rollicking girlfriend Ethel, I planted a few other essentials in big tubs. Ethel, well into her 80s when she fell in love with Robert, surrounded her house in Baltimore with dozens upon dozens of containers, flower pots, old coffee cans, buckets, anything that could hold water, all planted with flowers and vegetables. The little patio around her house was a riot of color, textures, fragrances, a garden as jolly as Ethel.

I planted garlics in one tub and last year’s dahlias in two more. But the tubs were not enough. I can’t imagine being too old to totter out the kitchen door to cut some fresh basil in my own garden.

I decided to build an herb garden just off the corner of the house, a few steps from the kitchen door. I chose a round spot about 12 feet in diameter beside the bird feeder. Rudy would be able to watch the herbs grow from his window.

Our little house is planted in the northeast corner of our old pasture. It was summer grazing for sheep, Claudia’s horse, and occasional beef cows. In more recent years, the pasture has become a home to more and more milkweed and other native plants we let grow all summer for pollenating insects, especially Monarch butterflies. The field was mowed only once a year when Cindy Downs comes with her ancient tractor and its ratcheting cutter bar.

So the spot I chose for a new garden is a thick matt of roots, a jumble of low field grasses and herbs dotted with the twisted old roots of birch sprouts that have been clipped off year after year. It was slow progress digging out this scalp of thick growth.

Anne and I dug with potato forks, a spade and Rudy’s long oblong tree shovel. Foot by square foot we pried up matts, shook off the soil and tossed the matts in a pile.

“This is good soil underneath,” I said. “We can put these matts in the ruts the well driller left.”

“I want to save these ferns. They’re hard to find in Rhode Island. Too sandy,” Anne said. Anne dug up a dozen unfurling Lady ferns, (Athyrium felix-femina).

The digging took us all afternoon on Saturday and half the day on Sunday. When we stopped for a water break, Rudy suggested we take some pain killer pills before we went back to work.

“Good idea,” Anne agreed. We both swallowed a couple of Aleve.

On Sunday afternoon, we spread a thick layer of Hank Letarte’s organic compost over the herb bed. Then we planted a circle of herbs: chives, a tall mint, oregano, rosemary, Tommy’s catnip, another rosemary, another mint, and chamomile in the center.

Anne watered the plants and frowned at the chamomile, its feathery stems bowed over. “That will grow better if you trim it. Make some tea,” she said.

When we were done, we still had room for basil and parsley when those seedlings get big enough to transplant.

We moved on to the new perennial bed Marianne and I covered with compost two weeks ago. This is a long sloping space west of the house. The area is a smear of yellow mud and rocks.

“Hard pan,” I told Anne. “The builder spread all the hard pan he dug out of the foundation hole.”

Hard pan is a rubberoid impermeable substance, a glacial relic that is almost as inhospitable to plants as solid granite.

“He should have taken that to a landfill,” Anne declared. She poked the hard pan with her shovel. “I’ll get a fork.”

Marianne and I had covered a quarter of the hardpan travesty with rich black compost from Hank Letarte’s organic farm in North Sandwich. Then we planted a poppy, a foxglove, a tall bee balm and a lavender, all natives.

Anne brought other gifts from her garden, penstemon with red tints to its long bladed leaves, three bunches of sunflowers and another short bee balm. We planted the driveway transplants with them, each plant mounded with compost several inches above the hardpan.

One of the great pleasures of a perennial garden, I’ve learned after years of living in a community of perennial expert gardeners, is that perennials need to be thinned out every spring or so. The plants dug and pulled out of thickets of bee balm and penstemon are ideal gifts or trades for other gardeners.

Now there are wide spaces between my new plantings. Anne and I sat on little lawn chairs and admired our work. I can imagine them in bloom. I can anticipate sharing them as the plants spread out and need thinning.

“The yellow coreopsis will look pretty with that pink penstemon,” she said.

Anne has been promoting native flowers, herbs and shrubs for years. She says they are essential for pollinators, native insects that we need to pollinate apples, squash and other foods. And those insects produce the millions of caterpillars that native birds need now in early spring to feed their young.

The native insect caterpillars are voracious. You’ve probably seen a few green Monarch worms munching their way through milkweed leaves. But these caterpillars, born in the Americas are finicky, Anne tells me. They cannot eat non-native plants, leaves from trees and shrubs brought here from Asia or Europe. Without natives, the caterpillars starve.

And so do the baby robins and other native bird chicks.

“A clutch of baby chickadees has to eat 350 to 570 caterpillars every day,” Anne says. She’s learned that from her friend Douglas Tallamy, a professor of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware. Tallamy is the author of Nature’s Best Hope, a New York Times bestseller that promotes conservation in our backyards. Tallamy champions native species not only for chickadee baby food but for a whole ecosystem of benefits.

Anne went home with a carload of the little Lady ferns. I should have given her some of the elegant ostrich ferns (Matteuccia struthiopteris) that are just unfurling under the oaks. At this time of year, these tall ferns are spectacular, their pale green fronds arching around emerging dark greenish-brown stalks of spores.

As Anne drove away, I remembered it was time to go down in the woods to look for a few viburnum plants.

Hobblebush or witch hobble (Viburnum lantanoides) is native in forests all along the Eastern seaboard. Our New England forest is almost as taciturn as natives like Rudy. Unlike mid-Atlantic woods that are edged in lavish dogwood and redbud each spring, our forests are a delicate dab of hawthorn (Crataegus rosaceae), one rare pink lady slipper, a trio of painted trillium.

Witch hobble is a white lace doily that grows in a family, like a crowd of Quaker ladies all wearing hand crotcheted white lace collars. The white clusters of flowers are 4 to 5 inch-wide disks cradled in elegant green leaves. The plants grow low to the ground on slender woody stems that sprout and grow as runners from the parent plant, just the right height to catch a witch’s long skirts when she tries to escape in the forest.

When I looked up this plant, I found it described as having a cardiod leaf, serrated on the edges. What is a cardiod leaf, I wondered.

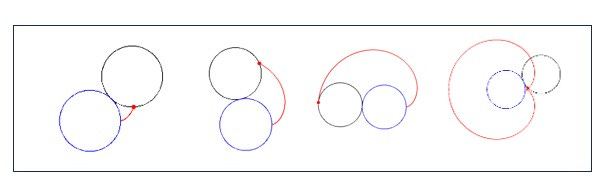

I learn from University of Georgia.com that “This falls under a special family of graphs called Limacon. We can obtain a cardiod by tracing the path of a point on a circle rolling around the circumference of another circle with the same radius.”

I couldn’t understand that. So I looked for images and found this cool animation by a creative geometer named Atomic Shoelace. And I figured out that cardiod comes from the Greek root for heart. Of course, my viburnum’s leaves are heart-shaped.

For a gardener, spring is a continuing feast of plants, wondrous new leaves, curious new names, the expectation of flowers to come.I’ll have to write more soon about my lifelong infatuation.Right now I need to run down to my neighbor Elaine’s driveway where she has set out some of her extra perennials.I want her arnica and those cute walking onions.

Cardiod animation, AtomicShoelace, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0., via Wikimedia Commons.

Spring has sprung in New Hampshire! Love that Anne and you are planting new beds for Rudy to see out the windows. Loved the photos! I wondered where your similes were that you craft so beautifully. Then ther it was.....Witch hobble turned into a "crowd of Quaker ladies all wearing crotcheted white lace collars." Thank-you!