Buds are swelling. Soon the forest canopy, whole mountainsides, will be tinted apricot, ruby, and rose. Oaks, sugar maples and beech are making anthocyanin to protect growing buds from burning ultraviolet light and still freezing nighttime temperatures.

“A bud is a cosmic investment,” Dr. Kevin Smith told my Wood Technology class at the University of New Hampshire.

Thin as a walking stick, his hair prematurely white, Dr. Smith did much more than talk about tree rings. The U.S. Forest Service dendrochronologist told us he practiced an organismal approach to his studies of wood.

Such a word, organismal. Every student in the class squirmed, thinking of sensual things. Dr. Smith went on. He explained that he studied the whole organism in its environment and through time. Dr. Smith also seemed to study the tree through a spiritual lens.

“The meaning of life,” he said, is the “energy capture by green leaves.”

As the sap rose in our trees this March, the maples unlocked the energy they captured last summer from the skeins of starch they stored in roots, wood, and the stem of every twig. The elixir of spring, flavored with vanillin, a growth stimulant, changed day by day until the sap turned ropey and white with proteins. Now buds are swelling. Within the next two or three weeks, they grow from 6 mm to 20 mm or more.

Buds are made almost a full year before they will open, before any human or tree knows whether the fall will be hot and dry or the winter cold and long. That’s what Smith called a “cosmic investment.”

Almost 20 years ago when I went down to UNH to study climate change and its impact on our forest, I decided I should visit the scanning electron microscope (SEM) lab to study Smith’s cosmic investments. I took along two or three buds from my sugar maples.

The buds were a little too long to fit in the SEM, perched on tiny steel pedestals. I cut one bud across the widest part near its base, a place where I thought I might see the stem of the embryonic leaf. I made the second slice across the slimmer top of the bud, where I assumed I would find the tip of a leaf. I glued these cross-sections of bud onto several stubs so I could peer into the buds from every angle.

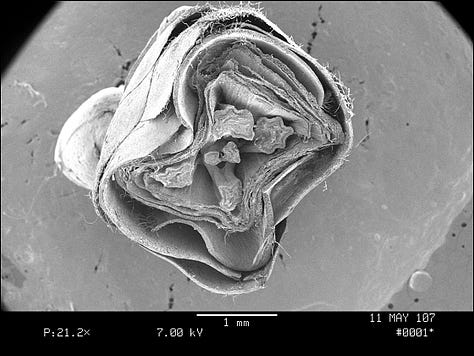

At just 21x, I looked down into something like a cup or bowl. It was more square than round. Thick layers of something like cardboard folded around one another and overlapped.

“Bud scales,” I realized.

There were eight or ten or a dozen scales. These soft blankets swaddled the embryo, the infant leaf in an inner chamber. But it didn’t look like an infant leaf. I couldn’t understand it, six projections, six little stalks rising from the base of the bud toward me. The little stalks were precisely situated, opposite one another and aligned at 90-degree angles from their companions. There were two smaller stalks in the middle, again opposite one another.

The stalks were rather star-shaped. In fact, the stalk on the right side of the chamber had, I counted, one, two, three, four, five points.

“A leaf, a maple leaf has five points,” I realized.

There were six embryonic leaves inside the bud, not one. And even in their infancy, they had five points and the same alignment of leaf to leaf that adult leaves have. I gasped.

I increased the magnification. At 150x, I examined the leaf that had the clearest view of the five points.

The leaf wore a crinkly outer blanket of thick-walled cells. Just under these light-colored cells, darker smaller cells ribboned the star shape.

Within each point lay a circular group of cells, a few soft looking cells in large gaping ovals and then tighter bundles of more angular cells, a bundle of these odd vessels for each tip of the leaf, a bundle that would make the vein that reaches out to each point on the flat plane of a leaf. I’d found the phloem cells and then xylem cells.

When I zoomed in again to 1570x, I could peer down into those xylem cells and admire the spiral thickenings on their inner walls. These were infant slinky toys that were already helping water molecules climb to the tip of the bud. Those wide gaping phloem cells were already transporting sugar molecules to growing tissues up and down the length of the bud.

I was astonished. Bud, leaf and indeed the whole tree follow, cell by cell, the same form, the same pattern for each species. I returned to the 22x view and could not stop admiring each star-shaped leaf, the six leaves in perfect symmetry, the swaddling bud scales.

I noodled around the bud visiting its base where sugar was stored in cubes like cloakroom cubbies. I moved along the walls of bud scales that seemed to need a good ironing. I found tiny hairs that exuded sap like tiny moisturizing misters.

Then I moved out along the bud to the tips of the leaves, a sheath of folded paper. This is called the plumule, an elegant word borrowed from French. The folded plumules, embryonic leaves, take up most of the bud. Their folds were creased and along those angled creases, I could see little bubbles of something. When I zoomed in on the bubbles, at 530x, the bubbles seemed to be emerging from the rippled surface of the leaves. It looked like Cinderella’s silk dress emerging from the 1950 Disney sewing basket when the mice made her pink gown, new silk spun for expanding leaves.

I was ready to go look at the plumule in cross-section. I peered into the bud’s tip at 25x. Now there were only two or three bud scales and they seemed thinner, like a papery basket. The leaf embryo or embryos within swelled to take up most of the view. And it was a confusing view, a crinkle of switchbacks.

The leaves were folded on each of the five veins like Japanese fans. The six fans of the six leaves jostled together as if the different leaves were stretching and pushing for more room. When I zoomed in on one curling fan, at 153x, I could see several layers of tissue and the delicate edge of a leaf where these came together. At each fold of the fan, I could see the xylem cells of the vein.

The inner wall of the bud scale caught my attention. I zoomed in to 1510x. The tissue looked thin as a silk curtain, wrinkled and pinched as if it had not yet been ironed. Like the leaf tissue, the bud scales were capable of growing longer and wider as spring swelled the buds.

Across our forests here in central New Hampshire, plumules are stretching, bud scales are expanding. On the last few days before the buds open, the plumules will grow beyond the reddish-brown bud scales. And then, on one warm sunny day, at the end of April or earliest May, the long oval bud will crack open.

Six wrinkled fans will emerge, the folds visible along each vein and in the deep cuts between the veins. The fans will open in a flat plane. The two smallest leaves will lie atop the four larger leaves. The leaf will be pale greenish-yellow tinged with reddish-brown anthocyanin. The surface of the infant leaves will catch the light and glisten.

Each new leaf will begin to capture sunlight and to make sugar. And at the base of each of the six infant leaves, new buds for 2026 will begin their cosmic investment.

Ω

Such amazing interesting slides! Wonderful Dr. Smith--"A bud is a cosmic investment." And "The meaning of life is the energy captured by green leaves." Can't say those words enough. Your similes and your descriptive verbs filled me with smiles. ",,.noodled around the bud where sugar was stored in cubes like cloakroom cubbies." "....the walls of bud scales that seemed to need a good ironing." Not just smiles, but laughing out loud with joy!